From The World View of Paul Cézanne: A Psychic Interpretation by Jane Roberts, Prentice-Hall 1977

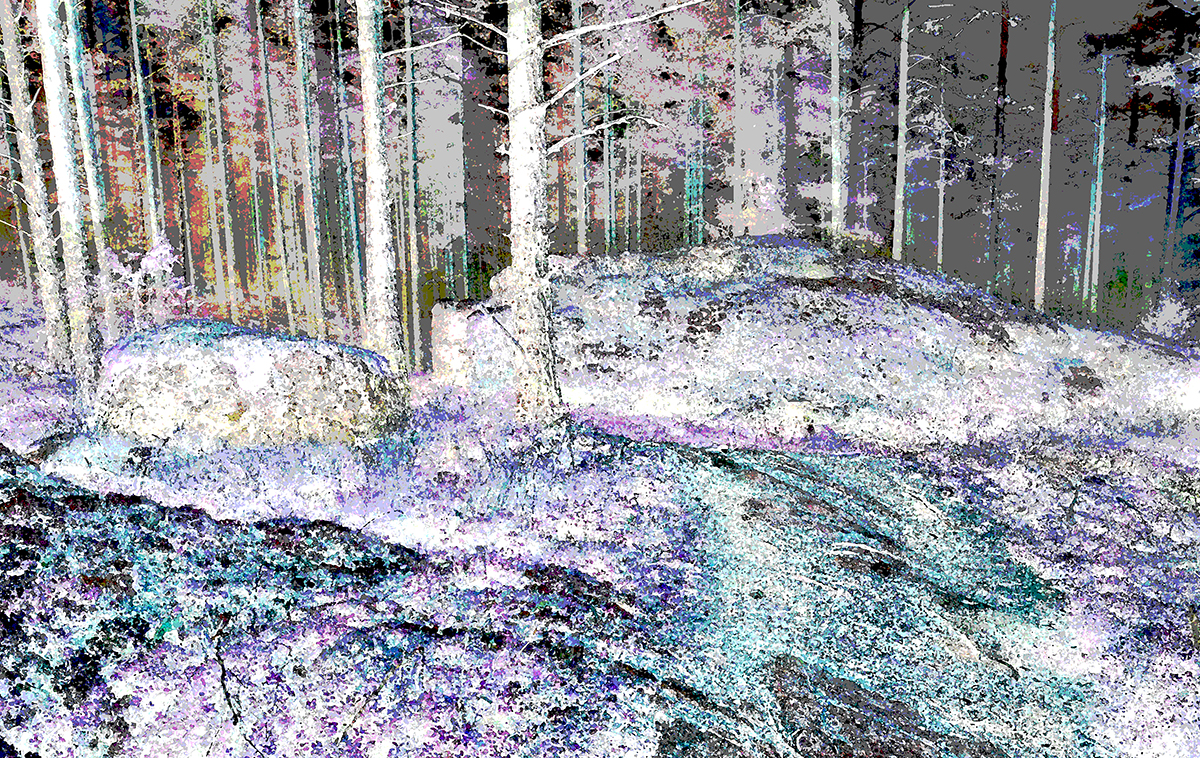

[143] I have a suspicion, never voiced before, that when a painter executes, say, a landscape, using a real one as a model, then changes also occur in the exterior model that are connected with his painting. A field, of course, is never the same, so when an artist begins a painting of one, he comes in on the field’s reality at a certain point, like entering a theater in the middle of the second or third act.

The action has been happening, but in his painting he begins at a certain point. By painting’s end, both artist and field have changed. That much is simple enough. But I have often compared my initial version of a landscape with the landscape as painted, and it seemed that other changes also happened that could not be assessed.

A relationship seems to be set up between artist, painting, and model; again, a triangular relationship that affects all three. Some kind of unknown sympathetic action, or attraction, perhaps, takes place. Surely the trees and rocks do not know that they are being painted; yet I swear that they are somehow changed as a result of the painting. It’s as if the artist’s mental images of them, objectified on canvas, are somehow superimposed then upon their physical images, though to an almost imperceptible degree.

Does the artist stamp his mental vision upon the [143] real world, altering quite physical conditions, even if minutely? If I use one rock as a model—a rock, say, that sits beneath a tree—but transpose it in my painting to a position somewhat to the right or left of the tree, the physical rock does not move to the position I’ve given it in my painting. Yet as I compared my landscapes—when they were finished but also through the various stages of completion—to the reality that served as model, it did seem to me that indications of such changes occurred.

These alterations were not visually apparent in usual terms. Yet their mental impression remained in my mind, so that in the real landscape I always mentally saw the rock where I had placed it in my painting. With my eyes open, the rock was in its physical position. When I closed my eyes, the rock would be in the paintings’s position. Sometimes though, with my eyes wide open and in good light, I would summon my “closed-eye mental image” at the same time, and then the rock seemed equally valid in either position, even though I knew that only one position was visually true. Yet I am certain, or almost certain, that in some way I cannot explain I altered the position of the real rock when I changed its placement in my painting.