[NOTICE: This is a draft of a work in progress. Please do not quote or copy without my permission. Thanks! — Gabriel Hartley]

Related Posts—Draft Chapters

Introduction

Two poems from Robert Frost’s first book of poems, A Boy’s Will (1913)—“Waiting—Afield at Dusk” and “Mowing”—stage an internal drama that would stay with the poet for life. This drama involves Frost’s internal conflict regarding what I would characterize as his dual allegiance to a kind of perceptual-philosophical realism and, in contrast, a visionary poetics of environmental engagement. Many of Frost’s poems stage and restage this conflict between what are too-easily characterized as natural-versus-supernatural or scientific-versus-delusional modes of perception and engagement. If “Mowing” appears to celebrate a hard-earned perspective apparently expressed in the poem’s penultimate line, “The fact is the sweetest dream that labor knows” (line 13), “Waiting—Afield at Dusk” seems to give us a very different sense of the sweetness of dream as it lays out “what things for dream there are” when individuals of exquisite visionary capacity allow themselves to be woven into the natural dreamscape that is waiting to enfold us if and when we are willing to participate in the crepuscular transitions that unceasingly call to us. The priority of poetic dreamwork in the two poems might, however, be reversed: the opening to dream prepared for in the work of “Waiting” is expanded even further in the factual dreamscape opened up in “Mowing.” The truth of the dusky dream achieves its validity in the labor of daylight consciousness. As we will see, one can learn to be “afield” at noon as easily as at dusk.

“Waiting—Afield at Dusk”

One of Robert Frost’s lesser-known poems, “Waiting—Afield at Dusk,” lays out the tuning-in process that allows for the shifts in consciousness that stimulate our connectedness with the world that envelops us. For reasons that will become clear, I am referring to this visionary process as fielding or, even better, enfielding—the process whereby one engages in the enfolding animations of a visionary geometry of interlaced patterns of connection. To be afield, then, is to be intricately conscious of the ways in which the circling swoops of swallows arcing through the evening sky weave us into patterns of environmental belonging. This, to my mind, is the poetic lesson of “Waiting—Afield at Dusk.” But let’s try to earn this vision by first winding our way through the words of the poem itself.

We begin with the title to see what we can gather from it: “Waiting—Afield at Dusk.” As we would expect, Frost often uses his titles to set the stage in various ways for what the reader is about to encounter in the poem. So here we learn that the poem will concern waiting, that someone is waiting for something or someone in a field at dusk. Or rather, the poem will deal with the condition of being afield, which strikes me as somewhat different from learning that someone or something is in a field. We are encountering the condition of being fielded, in a sense, of being woven into the field not only as a location but as a state of being, however momentary. The question comes up, then, of what this condition offers or predisposes one to. What sorts of things are implicit in being afield, being fielded, being laid open to the processes and encounters that might unfold for one who has been woven or has even woven oneself into this fieldedness?

And being afield or fielded at dusk, evening, just after sunset will certainly entail a different set of circumstances and relationships than being fielded at midday or midnight. This time of transition from one time of day or year or life to another is one of Frost’s key obsessions, one might say, and now and again frames the entire experience of—or even the entire purpose of—the poem at hand, the poetic world into which we are invited, the poetic meditation which we are drawn to entertain. Within this poem we enter the world in that moment when day turns to night, when day and night even out in this evening that marks the onset of the transition that the speaker is waiting for—the dreaming hour.

The first thing that grabs my attention once I enter the lines of this poem is its unusual syntax. Frost is generally known as a no-nonsense plain-speech poet, but that notion applies mostly to his choice of vocabulary and phrasing. And for the most part that description holds true for this poem as well. In his review of A Boy’s Will shortly after its English publication in 1913, Ezra Pound wrote: “Mr. Frost’s book is a little raw, and has in it a number of infelicities; underneath them it has the tang of the New Hampshire woods, and it has just this utter sincerity. It is not post-Miltonic or post-Swinburnian or post-Kiplonian. This man has the good sense to speak naturally and to paint the thing, the thing as he sees it. And to do this is a very different matter from gunning about for the circumplectious polysyllable” (Pound 72-73). The synchronicity of Pound’s satirical word choice “circumplectious” for my purposes here is nice, for this made-up word speaks exactly to the phenomenon I am characterizing as being afield or enfielding: the prefix circum-, of course, means “around, round about,” while the body of the word, “plection” or “plexion,” comes from the Latin plectere, “to weave, braid, twine, entwine.” Circumplection, then, perfectly describes the process of perceptual weaving and entwining that I see at the heart of the poem “Waiting.” “Circumplection” does not just characterize the theme of the poem, however. I have to work very consciously to get the spoken syntax right when I try to read this poem aloud. So my plan here is to work word-by-word, phrase-by-phrase through the poem to get some initial sense of its overall immediate statement, to unravel layer by layer the enfolding aspects of this poem. As a result, or so I hope, the workings of this twisted syntax might finally find a place within the themes of the poem itself.

Let’s begin with the first line, which immediately alerts us to the fact that we will have to pay close attention if we hope to get the simplest common spoken meaning of the poem before we can even start to think about the unspoken sense that Frost communicates in these lines. I will read the opening three lines before turning back to the first one because the first line by itself does not yet make sense syntactically until the sentence as a whole has unfolded a bit more: “What things for dream there are when spectre-like, / Moving among tall haycocks lightly piled, / I enter alone upon the stubble field . . .” (lines 1-3). Notice, first, that in terms of punctuation and extended syntax within the poem, the first sentence does not appear to be complete until the end of line eight and, second, that the five lines that follow the first three fill out the information we have gotten so far. I will return to those five lines once we have explored the opening three.

The poem, as we have seen, opens with “What things for dream there are,” a line that easily could have come from Yoda in the Star Wars movies because of its inverted syntax, ending rather than beginning with the subject and verb “there are.” If we rephrase these words in something resembling standard speech, we either have a question—“What things for dream are there?”—or the statement “There are some things for dream.” The rest of the poem is a list of the various things “for dream” that the speaker focuses on in his poetic meditation at dusk.

The poem appears to open according to the same syntactical procedure that we find in “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” (published ten years later in 1923)—“Whose woods these are I think I know”—but as we read on in “Waiting” we find that the phrase “What things for dream” functions differently from the elliptical function of “Whose woods these are.” “Whose woods these are,” being followed by “I think I know,” normally would read “I think I know whose woods these are.” It serves as the answer to an unstated question, “Do you know whose woods these are?” which itself is a response to an initial unstated question, “Whose woods are these?” I elaborate more fully on the depth and implications of this elliptical mode of presentation in my discussion of “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” but for now I simply wish to point out that while the opening lines of these two poems appear to follow the same syntactic structure and function, they are in fact very different. In “Stopping by Woods” we are presented with the elliptical structure evolving out of the bare algebraic statement “I think I know X.” The object of the speaker’s knowing, the elaboration on this syntactical X, is made clear: “I think I know [whose woods these are].”

“Waiting,” then, for a reader like me whose expectations have been framed by reading “Stopping by Woods” would appear at first to follow a similar pattern: “What things for dream” sounds like the relative clause that opens “Stopping by Woods” and so leads me to expect something like “I think I know” to follow in similar inverted fashion. But the rest of the sentence never completes such a pattern. There is no subject-verb structure to resolve the opening into a relative clause such as “whose woods these are.” Instead, we have an apparent exclamation: “What things for dreams there are!” The rest of the sentence simply lays out the circumstances under which such an elated mood might be generated. The implied question here, unlike “Stopping by Woods,” comes after rather than before the opening line. We do not begin with the question “What things are there for dream?” but arrive at this question after the exclamation: “Hey, there are some amazing things for dream here!” “Oh, yeah, like what?” And the poem, again unlike “Stopping by Woods,” goes on to answer that implicit but secondary question.

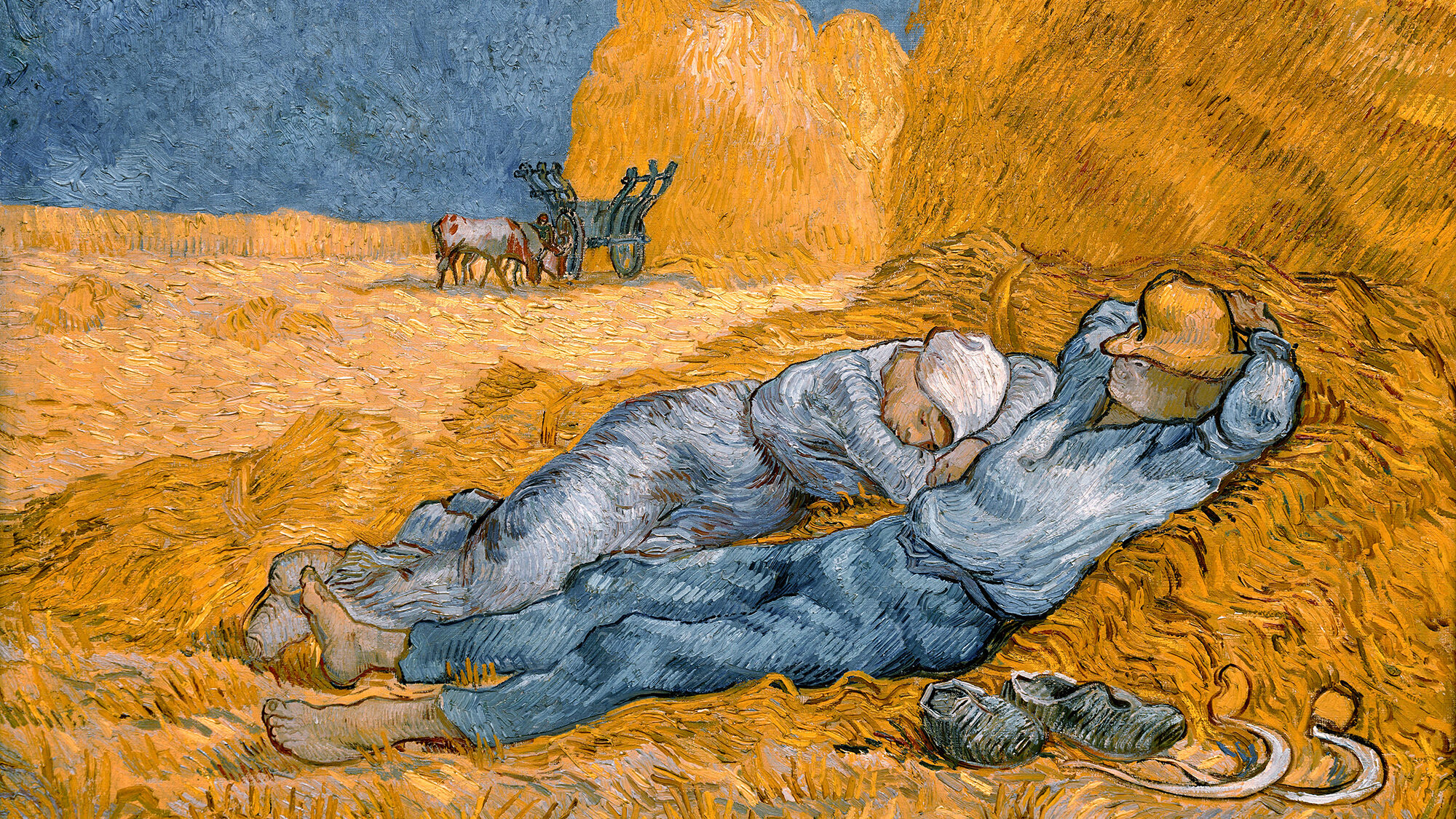

So, now to return to the opening line as a whole: “What things for dream there are when spectre-like . . . .” (The British spelling of “spectre,” appearing first in the 1913 British publication of A Boy’s Will, remains in the American versions.) The poem sets itself up as a celebration of this magical moment when such things can lead one into the poetic dreamlike state that the poem plans to unfold for us. But notice how the line at this point, not only in its enjambment but in its syntax as well, leaves us with the question, “Who or what is spectre-like?” The second line provides more detail regarding the setting, “Moving among tall haycocks lightly piled,” but has yet to link back up to the who or the what that is spectre-like. The third line, however, lets us know that it is the speaker, the “I,” that is afield at dusk alone awaiting spectre-like among the recent stubble for the things of dream to arise. The “I” or subject of the poem only appears once the enfielding circumplexious syntax is set in motion.

Lines 4-8 then read as follows:

From which the laborers’ voices late have died, And in the antiphony of afterglow And rising full moon, sit me down Upon the full moon’s side of the first haycock And lose myself amid so many alike.

Unlike the speaker in “After Apple Picking” (published in his collection North of Boston in the following year), the speaker here does not seem to have participated in this harvest but was presumably close by enough, or at least familiar enough with such work so as to hear the laborers’ voices which, having died of late, still seemingly resonate in the poet’s present experience of the recently-cleared field. (This situation will change once we enter the field of the poem “Mowing.”) He could not have had this same experience were the grass still standing, not just for practical reasons—you don’t sit down in the middle of an unmown field without risking the wrath of the farmers—but also in the sense that the speaker’s relationship to the first haycock positions him “amid so many alike” in this array of similarity in such a way that his senses are altered by the antiphonal full moonlight/fading dusklight view in which he loses himself. His position in relation to this haycock grounds him within the otherwise-dizzying motion of the fielding process that would leave him adrift among the sea of haycocks. He must find his proper spot, just as Carlos Castaneda does in The Teachings of Don Juan.

In lines 9-10 we discover the first thing that the speaker finds dream-inducing: “I dream upon the opposing lights of the hour, / Preventing shadow until the moon prevail.” As we have already seen, the antiphony of this twilight hour (line 5) conjoined with the rising of the full moon creates the atmosphere conducive to the poet’s hoped-for dream state. The choice of the word “antiphony” to describe the afterglow in the West (which in this situation would appear rather to call for the seemingly non-existent word “antiphany”—a state of opposing visual conditions) draws us into a kind of synaesthesia in which visual elements (contrasting atmospheric environments of light canceling shadow) suggest an aural back-and-forth song or argument of sunset and moonlight inspirations, a transformation of vision into sound—as if light speaks, sings, chants, and so, like the shaman’s drum or the chorale mass, leads the meditator into a deeper state of visionary awareness. In terms of the sounds of the poem so far, the antiphonal context involves the resonant absence of the laborers’ voices and the yet-to-be-sounded signatures of night, a hushed balance of resonance and anticipation that contributes to the production of the waited-for dream vision, a contrapuntal dance of vision transformed into sound transformed into vision.

Lines 11-13 give us the second dreamed-for thing: “I dream upon the night-hawks peopling heaven, / Each circling each with vague unearthly cry, / Or plunging headlong with fierce twang afar.” Notice that the poet does not simply dream of but dreams upon these night-hawks. While the word “upon” here might seem like a typical poetic archaism, I think that Frost is suggesting an important distinction between of and upon. To say that someone dreams of something simply fills out the object (both logically and grammatically) pertaining to the dreaming: “This is what I am dreaming of; this is the thing that populates my dream.” But dreaming upon something suggests instead not that the object is simply the complement of the dream action but, rather, the inspiration for or instigation to the dream state, calling to mind the common expression “to wish upon a star.” The star becomes the wish-dispensing or fulfilling agent, not simply the object of my perception but the producer of it. Just so, the antiphonal lights of the previous lines and the night-hawks of these lines are not the objects of the poet’s dream but the creator of it. The poem, then, involves a drawing together of the various elements of this magical moment responsible for the poet’s visionary (and auditory) transformation from daylight to moonlight consciousness.

Nighthawks, a species of the nightjar family, appear at dusk as they circle in the twilight sky to eat bugs. Frost does not describe them as beings of the sky or “the heavens” but creatures who people heaven. These word choices suggest that the poet seeks a familial relationship with heavenly entities whose “unearthly cry” now fills the otherwise unpeopled soundscape of the speaker afield. Their cries and fierce twangs, as well as their circling, plunging arcs, create another layer of the fielding experience of this weaving-into-dream that the poem enacts. The bats, the third “thing of dream” (lines 13-17), add an antiphonal layer of silence in their muteness—a lack of sound that still registers in the soundscape of this evening, as they create their own sky patterns in their pirouettes that they themselves, in their “purblind” lack of sight that nevertheless makes out his “secret place,” add with “the last swallow’s sweep” (the fourth thing of dream) to the visual field of the poem’s enfielding function.

And fifth in this train of dream inducements is the sound of crickets, presumably (lines 18-22):

. . . and on the rasp In the abyss of odor and rustle at my back, That, silenced by my advent, finds once more, After an interval, his instrument, And tries once, twice, and thrice if I be there;

Just as the looping through air of the birds and bats creates a portal web of visual enchantment, the sounds weave their own web in this hide-and-seek play of the speaker who sinks into this dreamlike abyss, as if melting into his twilight-moonlight environment of sights, sounds, and now smells.

Sixth among the things of dream comes “the worn book of old-golden song,” a treasury of verse, it seems, that might record similar dream songs as the one the poet is now spinning out of twilight, possibly, one might expect, as further incitement to take part in this chorus of poetic visionaries. But this book “I brought not here to read, it seems, but hold / And freshen in this air of withering sweetness” (24-25). The poet’s current conjuring of this atmospheric dreamscape nourishes the very poetic community that schooled the poet in the first place. Through this visionary act of giving oneself up to the fielding of twilight inspiration (inspirited by this enfieldment), the poet simultaneously draws from and adds to the lyrically-transformed community in such a way as to add their own lines to the worn book of old-golden song. The human community itself blossoms in this transformative flow of dusk.

Yet this communal fusion of nature and humanity is not the final end. The seventh thing of dream is the most conjuring of all: “But on the memory of one absent most, / For whom these lines when they shall greet her eye” (lines 26-27). These inversions of syntax could be rewound as follows: “The thing that induces me to dream-vision the most is the girl whose current absence creates this poetic anticipation of the moment when, the two of us together, her eyes shall draw her into the poetic enfieldment that enfolds me now.”

To return to my opening comments regarding Frost’s syntax in this poem, I would now argue that his twisted syntax is at one with the enfolding dreamscape of one who is afield in the sense that the poem has in large degree created within itself. Just as the tall grasses of the field have been cut and lightly stacked together into a moonlit array of haycocks that now punctuate the field and recreate its texture, the phrases within the poem fold and unfold into a similar array that momentarily arrests and then redistributes the lines of communication of the poem in unexpectedly enfolding ways. The cutting of the hay exposes the otherwise safely hidden insects and rodents that are now laid bare for the nighthawks, the bats, and the swallows, whose looping swerves encircle and redistribute the previously indeterminate space of heaven. The laborers’ resonating silence has created the space for this anticipation of lovers’ union by way of enfielded song. The poet afield is at once the center and circumference of this dusklit transitional dreamscape.

“Mowing”

One of the environmental sources that, due to the nature of our human physical-etheric sensorium, reflexively affect us (consciously and unconsciously) is the field of sound. For poets, of course, the realm of sound is a critical arena for worldly engagement and expression. The question naturally arises how one might mimic or incorporate or otherwise respond to the sounds of the world around us. As Henry David Thoreau famously put it in Walden, “If we respected only what is inevitable and has a right to be, music and poetry would resound along the streets.” So, not surprisingly, attention to the sounds of one’s environment becomes a critical theme for Frost, as these two poems reveal.

The question of our relationship to sound animates “Mowing” right from the start: “There was never a sound beside the wood but one, / And that was my long scythe whispering to the ground” (lines 1-2). And, typically for Frost, this opening line leads to more questions than conclusions. First, there seems to be quite a bit of hyperbole at work here depending on how we are meant to contextualize these words. Was there really only one sound beside the wood? Certainly there were the sounds of birds and insects and an occasional breeze, and there were likely to be farm animals within the range of hearing of this grass-cutting boy, and possibly there were even other cutters in the field. The line suggests its own completion with the addition of extra words, so as to read “There was never a sound beside the wood but [the] one [that caught my attention or that mattered to me].” But this extrapolation of mine depends on the assumption that the speaker desires to see things as they really are. And yet an alternative mode of focus or attention is at work here in the poem right from the start: for the boy with scythe in hand, there is only one sound beside the wood—the whispering of his scythe itself.

Another question that arises in these opening words is what the speaker means by the word “beside” when he says “beside the wood.” Is this “beside” as in next to or “beside” as in other than? An answer to this question complicates any answer to the first question: if the speaker means “next to,” then we are still talking about one sound in the entire soundscape. But if he means “other than,” then the sounds of the wood are also in play here. So the poem immediately presents us with a terminological indeterminacy that it might not resolve. What we do know, nevertheless, is that this boy has entered into some kind of heightened perception and sense of connection: he engages with his scythe, this tool that has become a prosthetic extension of his own body in the work of the day, to such a degree that he perceives the communicability of the scythe, an object that communicates with the earth, with the planetary ground of our being—but it does not communicate directly with the boy:

What was it it whispered? I knew not well myself; Perhaps it was something about the heat of the sun, Something, perhaps, about the lack of sound— And that was why it whispered and did not speak. (lines 3-6)

And it is this incapacity to communicate directly with his whispering scythe that draws the speaker into a poetic-visionary mode of perceptive extensibility, into wondering what and to whom it might whisper. The poet is left only with the possibility of guessing, of projecting, it would seem, onto the consciousness of the scythe, what its motives and intentions and instigations might involve.

The first hint in the poem of the conflict I have previously mentioned concerning the competing impulses to “realistic” versus “visionary” modes of consciousness comes in the next lines: “It was no dream of the gift of idle hours, / Or easy gold at the hand of fay or elf” (lines 7-8). If we are to imagine some kind of narrative continuity in the sequence of poems that make up A Boy’s Will, then “Mowing” seems to be speaking directly to the consciousness embodied in “Waiting—Afield at Dusk,” which appears before “Mowing” in the sequence. As we will see, the boy afield in “Waiting” would appear, from the perspective of the voice of “Mowing,” to be just such a dreamer who can afford the gift of the idle hour of dusk. Depending on how we read line 7, we are left with at least two different possible approaches to this dream: one, this recognition of the scythe’s whispering is neither a dream nor a fairy tale—this is “no dream” as in not a dream. Or two, this is no dream appearing as a gift of idle hours but rather a dream resulting from the labor of the day—this is “no dream” of that time of day but rather of this time of day. The first approach challenges the validity of idle dreams as sources of truth while the second challenges our usual assumption that dreams only occur in idle hours. For the first approach, dreams are no better than fairy tales born out of idleness for those who prefer not to work but let the fairies and elves do their work for them; for the second, dreams can be the products of sunlit labor. The first maintains the hierarchical separation of “truth” and “dream”; the second allows for the extension of “dream” into “truth” or even the subsumption of mundane truth into the higher truth of dream.

These two possible understandings of the relationship between dream and truth give us at least two different approaches to the next lines:

Anything more than the truth would have seemed too weak To the earnest love that laid the swale in rows, Not without feeble-pointed spikes of flowers (Pale orchises), and scared a bright green snake. (9-12)

For the understanding according to which truth is greater than dream, then the point seems to be that we must put aside dreams if we are to honor the earnest hard-won truth of labor in the field. The “more than” would be any product of idle dreaminess. Anything more than this is too weak. Yet from the perspective that sees dream as a mode of truth, the “more than” would be the imposition of narrow views concerning the relationship between truth and dream, a weak and unnecessary restriction of our understanding of the greater truths of dream. This perspective gives us a greater scope of consciousness when approaching statements such as line 13: “The fact is the sweetest dream that labor knows.” There is no utilitarian division between and reduction of dream to fact here; fact is dream, the sweetest dream that labor knows. And within the scope of this enlarged consciousness, the boy remains firm in his apprehension that his scythe in the final line does, in fact and not as projection, whisper: “My long scythe whispered and left the hay to make” (14). This is no “dreamy” personification but an extension of consciousness and expression to all that lies beyond the restricted realm of merely human consciousness. The speaker takes the less-traveled path of understanding, and that makes all the difference.

From what I would take to be the restricted perspective that reduces dream to fact, “Mowing” would appear to be a rebuke of the consciousness expressed and produced by “Waiting—Afield at Dusk.” As we have seen, this perspective would see the boy in “Waiting” as an idle dreamer estranged from the truth of the daytime laborer whose muted activities nevertheless resonate in the antiphonal lights of dusk and full moon. But the speaker in “Mowing” never, in fact, engages in such a reduction. If anything, “Mowing” extends the magic of dreaming at dusk into the labors of the day. The sweet dream fact of this poem is that any time is the right time for dream when we have allowed our consciousness the freedom to dream of such a fact. Dusk allows for a certain mode of allowing oneself to be afield, to be fielded or enfielded. But more magical still is the awareness that the sun at high noon does so no less.

Some References:

Faggen, Robert. “The Fact is the Sweetest Dream: Darwin, Pragmatism, and Poetic Knowledge.” Robert Frost. Harold Bloom, ed. Chelsea House, 2003, pp. 219-69.

Giles, Paul. “From Decadent Aesthetics to Political Fetishism: The ‘Oracle Effect’ of Robert Frost’s Poetry.” American Literary History 12:4 (Winter 2000): 713-744.

Haynes, Donald T. “The Narrative Unity of A Boy’s Will.” PMLA 87:3 (May 1972): 452-464.

Howlin, Jeff. “The Psyche at Dawn and Dusk.” The Santa Cruz Psychologist. Website: http://www.santacruzpsychologist.com/blog/2013/the-psyche-at-dawn-and-dusk-a-look-at-crepuscular-moments/

Pound, Ezra. “Review of A Boy’s Will.” Poetry 2:2 (May 1913): 72-74.

x

Leave a Reply